Credit: João Bizarro

Five hundred years ago, the Jews of Portugal were expelled. Their roots in Lisbon, Oporto, the Algarve and the mountains of Belmonte, reaching back thousands of years, were wiped from history.

Fast forward to 2024 and the community of Oporto, (Porto) the second largest city in Portugal, now comprises more than a thousand Jews from more than 30 countries around the world. It has flourished and revitalised over the past decade after nearly a century of sleep.

Jewish News was invited to visit the small but determined group of board members whose sole purpose is re-establishing a community, albeit very quietly, cautiously and in many ways, very secretly, often remaining anonymous for their own safety.

Their caution is understandable – a brief look at the tumultuous history of the country offers a glimpse of the horrors its Jews have faced, making its current determined expansion even more extraordinary.

Oporto, August 2024. Credit: Michelle Rosenberg

At the end of the 15th century, the Jewish community in Portugal took in tens of thousands of Jews who had been expelled from Castile due to the Spanish Inquisition. By royal decree they were forced to wear a six-pointed star on their clothes.

For a time, Jews and Catholics lived side by side. Despite contributing hugely to the country’s economy and culture, it wasn’t long before the prejudice and culture of intolerance from the Spain spilled over into Portugal.

In 1496, Manuel I of Portugal issued an Edict of Expulsion of the Jews. Their choices were limited: leave or convert to Catholicism and become ‘new’ Christians. Those that couldn’t afford to leave stayed, secretly keeping their faith in private, with thousands becoming Marranos, (a derogatory term meaning ‘pigs’) or crypto-Jews.

Credit: Michelle Rosenberg

They were still subject to punishments for heresy including being burnt at the stake. The Portuguese Inquisition was only disbanded in 1821.

Then there is the case of the so-called Portuguese Dreyfus: Captain Artur Carlos de Barros Basto. Born into a Christian family in 1887, his grandfather had held firmly to his Jewish roots. Basto converted to Judaism before a rabbinical court in Morocco and made it his life’s work to re-establish a Jewish community, which then numbered only eight families.

A visionary leader dedicated to bringing former ‘crypto-Jews’ back into the fold, he was instrumental in the building of the Kadoorie Mekor Haim Synagogue, founded in 1923 and completed in 1938, financially supported by a wealthy Jewish family from Hong Kong.

The largest synagogue in the country, it later provided shelter for about 5,000 Jewish refugees who arrived in Oporto in 1939 and 1940, seeking a temporary home after fleeing Nazi persecution in Europe, before emigrating to countries including Canada, the USA, Venezuela, Haiti and the UK. None wanted to stay in Portugal; none wanted anything more to do with Europe.

After the war, there were hardly any Jews left in Portugal. Emigration and assimilation played their part, and an anonymous letter sent to Basto, accusing him of homosexuality, destroyed his military career. His actions in circumcising some of those crypto-Jews were deemed immoral by the army.

He died in March 1961; in a poignant twist of fate, his economist grand-daughter Isabel Lope Basto, is now treasurer of the current Oporto Jewish community. Following the political upheaval of revolution in Portugal in 1974, about half of the country’s Jewish population emigrated to Israel, Brazil, Canada and the USA.

Art gallery images, Synagogue Kadoorie Makor Haim

It is against this backdrop that Jewish News has been invited to meet the small group spear-heading hugely ambitious attempts to revive the community, which in 2012, was minuscule, with only 400 euros to its name. We meet in the gallery room of the synagogue, surrounded by artworks depicting the history of Oporto’s Jews and welcomed with a large bottle of traditional port.

With Brazilian and Polish Jewish roots, Gabriel Senderowicz, president of the Jewish community, tells Jewish News: “Ten years ago there was nothing here and today there is everything. In 2012, the Jewish community of Oporto existed in theory, as an official organisation, but in practice there was no community, just an empty synagogue with a few dozen Jews scattered around the city.”

Gabriel’s wife Gabriela is the journalist who runs Portuguese Jewish News and is president of B’nai B’rith Portugal.

Jewish Museum, OPorto

Buoying the return of the Jews was the 2015 passing of a law allowing descendants of Sephardic Jews who were expelled in 1492 to apply for Portuguese citizenship.

Oporto now has a full synagogue, consecutive minyan for eight years, two museums, kosher restaurants, a kosher hotel, a mikveh, internationally awarded history films and a cemetery founded in April 2023 (the first Jewish cemetery in Oporto in 500 years, the previous one destroyed during the Inquisition).

Porto’s Jewish Museum has welcomed around 130 thousand teenagers, (around 13 per cent of the total teenage population in Portugal) from schools in less than three years. The community also built a second synagogue for a largely French student community and helped build the largest Chabad centre in Europe.

Senderowicz points out that the museum is free. “We pay for everything: the museum, the staff, the police, the vans that bring children from poor schools across the country, sometimes even the snacks that hungry children need.”

Aimed primarily at the national and international Jewish community, the museum has a room dedicated to modern antisemitism, a cinema and a kosher port wine cellar.

The community has made several films, including “Sefarad” (about the history of the community over the last 100 years), “1618” (about the Inquisition in Porto, it is the most internationally awarded Portuguese film ever distributed in the United States) and “1506” (about the genocide in Lisbon).

Oporto. August 2024. Credit: Michelle Rosenberg

Interfaith plays a strong part of their ongoing work, with Senderowicz describing the Bishop of Porto as “the best friend the community has in Portugal”.

Oporto Jewish community provides financial support to all of Keren Hayesod’s projects, as well as to the activities of the Israeli embassy in Portugal. Perhaps their most important ongoing work is the processing of the records of the Inquisition.

None of this would have happened without David Garrett, until recently the largely unsung hero of Oporto’s Jewish community. For many years he didn’t give a single interview or allow his photograph to be taken.

A genuine force of nature, Garrett says his family’s history in Portugal goes back at least 200 years. After two days of speaking to him, Jewish News strongly suspect those roots go back even further.

He says: “Our Yom Kippur event was described by Israeli ambassador Oren Rozenblat as the best he had ever seen. The parents of the French students in the community always thank us for the fact that their children return to France much more religious than when they arrived. In short, we did the best we could.”

Jewish News’ Michelle Rosenberg outside Kadoorie Makor Haim, Oporto, August 2024.

While Gabriel Senderowicz notes that they are proud that “in 10 years, the community has not only been reborn, but has experienced exponential growth” the revival has not welcomed by all.

As reported by Jewish News, following anonymous complaints, in 2022 the community’s rabbi was arrested and humiliated while an “unexpected search” was conducted at the community’s institutions – including the Kadoorie Mekor Haim synagogue.

Senderowicz claims the Oporto Jews were victims of a “very serious case of antisemitism perpetrated by a collusion between state agents, police, journalists and anonymous whistleblowers.”

Visitors to Kadoorie Makor Haim. Credit: João Bizarro

With gratifying historical symmetry, it is noteworthy that while Captain Artur Carlos de Barros Basto didn’t have the law on his side, David Garrett is an exceptional criminal lawyer, doing his utmost to formally close any loopholes that could legally impede the community from surviving.

Thus the community filed a petition with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg against the Portuguese government, claiming “brutal actions” against it as well as damage to its reputation, calling it “21st-century blood libel”.

It claimed “millions of documents and private correspondence relating to the community and its members were taken from the community’s institutions, just as the Inquisition did when it framed members of the Jewish community and invaded their homes and workplaces, based on anonymous complaints.”

Credit: João Bizarro

Due to recent events and for its own safety, the Jewish community has had to close its institutions to the general public. Though young people continue to visit the Jewish museum and the Holocaust museum of the Porto community in significant numbers throughout the year, the synagogue and museums are open to the general public only once a year —on The European Day of Jewish Culture, marked by more than 20 communities in Europe every September.

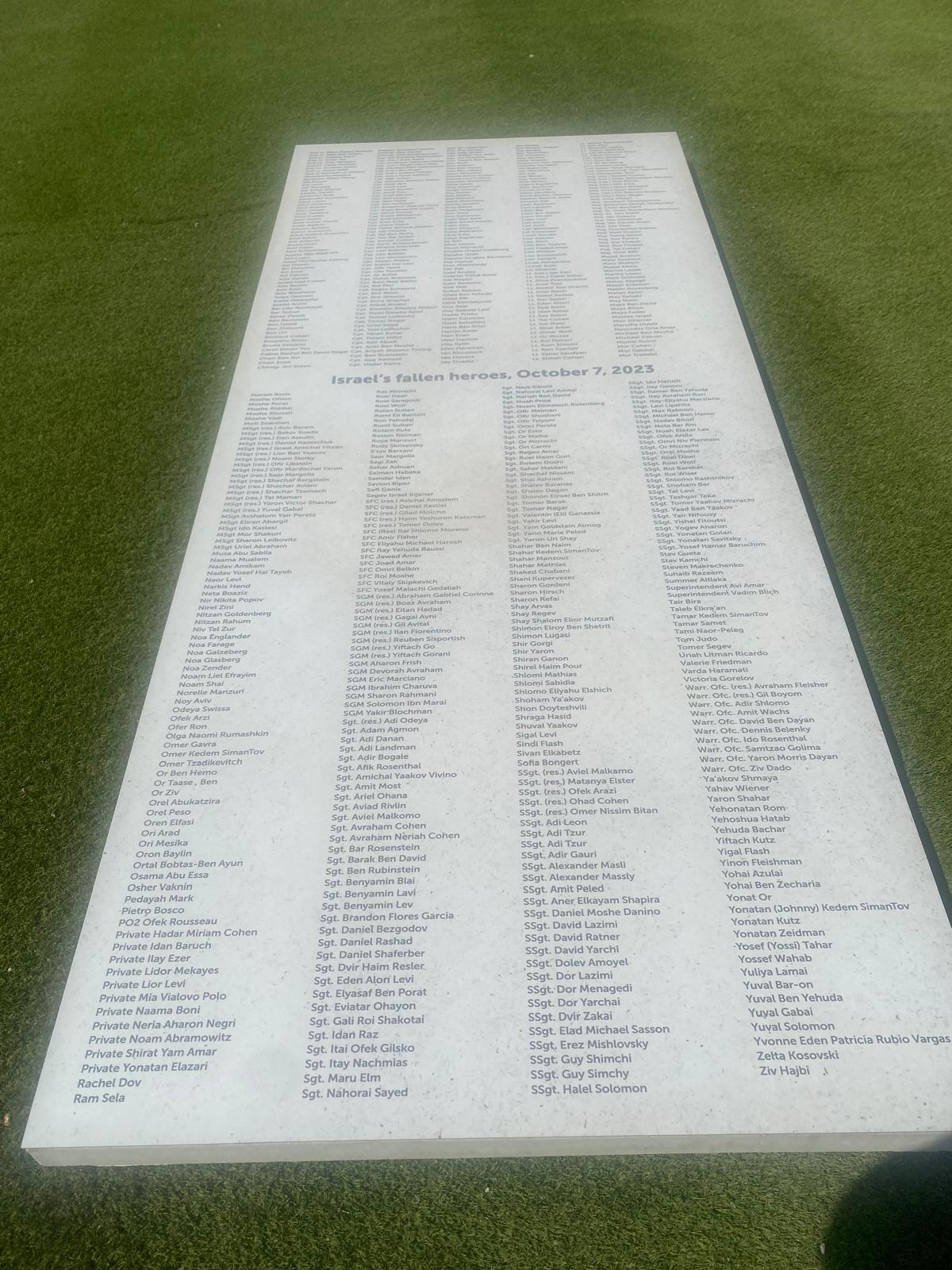

Commemorative stone to those murdered on October 7th 2023. Oporto Jewish Cemetery. Credit: Michelle Rosenberg

This year, more than 1,000 people visited the synagogue and witnessed the inauguration of an epigraph, dedicating the assets of the Jewish community in Porto to the Jewish Agency, to be used if the Jewish community in Porto ceases to exist.

The ceremony took place in a room documenting the rise of antisemitism in Portugal over the past decade, starting in 2014. Incidents include graffiti on a synagogue fence, demonstrations demanding the expulsion of Zionist “apartment owners” from Porto and the suspected attempted assassination of a Jewish-French dental student last year. The incident happened after the student, together with dozens of his classmates, signed a petition calling on the French president to force Portugal to give posthumous justice to Captain Barros Basto.

There is, however, hope, optimism and determination.

Just over five centuries after the Edict, the Jewish and Catholic communities of Oporto signed a friendship and co operation protocol agreeing to work together on joint charitable projects.

Painting of outside of Kadoorie Makor Haim.

Oporto’s last Jewish cemetery was destroyed in 1497 but its new grounds, hidden behind anonymous security gates, was inaugurated by the chief rabbi of Israel, Yosef Shenim. Currently, its only engraved stone is one movingly dedicated to those murdered on October 7th. Otherwise, it remains empty, awaiting the first Jewish body in centuries to be buried on consecrated ground.

There is some way to go until Jewish bakeries are front and centre on the main streets of Oporto; for now, challahs are baked and sold from the synagogue; kosher food at Hotel da Música is served in foil packaging at three tables in a quiet corner and Gabriel tells us that he walks the streets freely wearing his kippah.

Services are busy, families are growing and the community is staunchly determined to thrive.

Most importantly, it is determined this time to survive.

This article was originally published in the Jewish News - Britain's Biggest Jewish Newspaper Online, in a partnership between the Jewish News and The Portuguese Jewish News.