Credit: Sefira Lightstone - Chabad

The Jewish community in Syria has a long and rich history dating back millennia. Over the centuries, Syrian Jews have lived in several important cities, such as Damascus, Aleppo and Qamishli, and have been an integral part of the country's social, economic and religious life. The community was predominantly Sephardic, with some influences from Mizrahi Jews, that is, from more eastern traditions.

Ancient and Medieval History

The Jewish presence in Syria dates back to antiquity, especially after the Babylonian exile and the conquests of Alexander the Great. During the Hellenistic period, Syria, especially Damascus, became an important commercial and cultural center, and Jews were part of the local population. In the Roman and Byzantine period, Jews continued to live in the region, and Syria was a dispersal point for several Jewish communities.

Ottoman era (1516–1918)

Under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled the region for more than 400 years, Jews in Syria were considered one of the "protected nations" (millet), which gave them a certain religious and social autonomy, but also subjected them to restrictions, such as the payment of special taxes. During this period, many Jewish communities flourished, particularly in Aleppo and Damascus, which became centers of religious learning and Jewish culture.

In Aleppo, for example, the Jewish community was prosperous, with religious schools, synagogues and active commerce. Many Syrian Jews were traders, craftsmen or involved in the textile industry. The community was also known for its scholarship, with influential rabbis and a rich tradition of Torah and Talmud study.

20th century and changes

With the end of the Ottoman Empire and the advent of the French Mandate in Syria (1920-1946), the political situation changed. During the French Mandate period, the Jewish community was relatively protected, but the political climate in the region began to change with growing Arab nationalism. In 1947, with the creation of the State of Israel and rising tensions in the Middle East, Jewish communities in several Arab countries began to face persecution, and many Syrian Jews began to emigrate.

In 1947-1948, following the Arab-Israeli war, most of Syria's Jews were forced to leave the country. Those who remained lived under severe restrictions and faced increasing hostility. Syrian authorities imposed laws that restricted Jewish freedom of movement and property ownership. Additionally, synagogues and Jewish schools were closed, and most Jews who remained in the country faced discrimination.

Jewish Community in the 21st Century

The Jewish community in Syria has practically disappeared in recent decades. In the 1960s, during the regime of Hafez al-Assad, emigration continued, and Syrian Jews dispersed mainly to countries such as the United States, France and Latin America. The vast majority of the Jewish community left the country after the rise of the Bashar al-Assad regime, especially after the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, which devastated much of the country's infrastructure.

Currently, there are only a few Jews left in Syria, mostly in Damascus, but the community is extremely small and lives under anonymity due to political and security circumstances.

Religious and Cultural Aspects

The Syrian Jewish community, particularly in Aleppo and Damascus, had a rich religious tradition, with many Jews specializing in religious and medical studies. Syrian Jewish literature included its own liturgical texts and a unique style of prayer. Synagogues were centers not only of prayer, but also of teaching and culture.

Syrian Jewish cuisine is another important part of the cultural heritage, with dishes such as kubbeh (meat dumplings), hummus, falafel and other dishes typical of the region, which have been passed down from generation to generation.

Arabic was the predominant language among Syrian Jews, although many also spoke Ladino (a variant of Spanish spoken by Sephardim). The Syrian Jew had a very distinct cultural and religious identity even though he lived in an Arab Muslim environment.

Legacy

The legacy of the Jewish community in Syria, although very limited today, is still remembered by many descendants of Syrian Jews around the world. The Syrian Jewish diaspora keeps its history alive through its cultural and religious traditions and its contributions to the communities they moved to, especially in countries such as the United States, Brazil and France.

In summary, the Jewish community in Syria had a significant and influential presence until the middle of the 20th century, but its continuity was interrupted by turbulent political and social events, resulting in the near extinction of this community within the country.

Synagogues in Siria and Rabbis

Synagogues in Syria, especially in large cities such as Damascus, Aleppo and others, have played a central role in the religious, social and cultural life of Jewish communities over the centuries. Although most synagogues were closed or destroyed following the mass emigration of Syrian Jews beginning in the mid-20th century, the legacy of these synagogues is still remembered, and some of them have a significant history.

The Central Synagogue of Aleppo. Credit: Govorkov- Wikipedia

Here are some of the most important and notable synagogues in Syrian history:

1. Job Synagogue (Damascus)

Located in the old city of Damascus, the Synagogue of Job is one of the oldest and most historic synagogues in Syria. Traditionally, this synagogue is believed to have been built on the site where the biblical prophet Job was buried, although this cannot be definitively confirmed. The synagogue was famous for its architecture and the religious tradition that was maintained there. It was a place of pilgrimage for many Syrian Jews, especially during religious festivals.

During the period of French rule in Syria, the synagogue was restored several times, but following increased political tensions in the 1940s and the mass emigration of Syrian Jews, the site was abandoned and suffered vandalism.

2. Aleppo Synagogue

Aleppo, which was one of the most important cities for the Jewish community in Syria, was home to several synagogues. One of the most notable was the Aleppo Synagogue, also known as the Synagogue of the Prophet Elijah. It was a center of community life, with daily liturgical activities, religious teaching, and a strong presence of scholars and rabbis.

Unfortunately, the Aleppo Synagogue was destroyed during the Syrian civil war. During the final years of Hafez al-Assad's regime, the Jewish community was drastically reduced, and the Aleppo synagogue, which was already in decline, was virtually abandoned. In the 2012 civil war, it was destroyed, along with many other religious and historical structures in Aleppo.

3. Al-Mazzeh Synagogue (Damascus)

Another important synagogue in Damascus was the Synagogue of al-Mazzeh, which was also associated with the cult of Job. The synagogue was located in a traditionally Jewish area of the city and served as a center for prayer and study. Like other synagogues in the city, al-Mazzeh suffered decline as the local Jewish community dwindled and was abandoned in the following decades.

4. Al-Qaryatayn Synagogue (Qamishli)

The city of Qamishli in northern Syria also had a small Jewish community and synagogue. The al-Qaryatayn synagogue was not as well-known as those in Damascus or Aleppo, but it was of great importance to the Syrian Jews who lived in that region. With the exodus of Syrian Jews in the 1940s and 1950s, the synagogue was also decommissioned and abandoned.

5. The Hama Synagogue

The city of Hama, although smaller in terms of Jewish population, also had its synagogue, where the local community gathered for prayers and religious celebrations. The history of the synagogue in Hama is less documented, but it is believed to have been part of the city's religious life until the Jewish exodus in the mid-20th century.

Architectural Features of Syrian Synagogues

Synagogues in Syria were generally simple, but with an understated beauty typical of Sephardic and Mizrahi synagogues. They often followed the traditional Arabic architectural style, with arches, internal courtyards and carved wooden details. In some synagogues, especially in Aleppo, there was a rich decoration with mosaics and inscriptions in Hebrew.

Furthermore, Syrian synagogues had a special feature: a focus on Torah reading and liturgical chants traditional to the region. Many synagogues had a sefer torah (Torah scroll) of great historical and spiritual value, often used in important rituals.

Destruction and Disappearance of Synagogues

With the mass exile of Jews from Syria following the creation of the State of Israel, synagogues began to lose their religious functions. During the 1960s and 1970s, with political repression and growing tensions between Jews and Muslims in the region, many synagogues were closed or abandoned. The situation worsened with the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, which resulted in the destruction of many historic and religious buildings, including synagogues.

In 2012, the Aleppo Synagogue was partially destroyed during clashes, and other synagogues in Damascus and Aleppo were damaged or vandalized. Synagogues in areas that still maintain a small Jewish population, such as the Synagogue of Job in Damascus, are now little more than ruins or places of memory, without regular religious activities.

Legacy and Memory

Although synagogues in Syria have almost completely disappeared, the memory of their importance remains alive among Syrian Jews throughout the world. Descendants of Syrian Jews in countries such as the United States, Brazil, France and Argentina often remember the synagogues and religious traditions that were centered in these places. Some Syrian Jews have also made efforts to preserve documents and liturgical items from their synagogues, including sefrei torah and prayer books, to ensure that the legacy of the Syrian Jewish community is not forgotten.

In short, Syria's synagogues, although now largely decommissioned or destroyed, represent a vital part of the religious and cultural history of the Syrian Jewish community. The disappearance of these synagogues reflects the dramatic transformations the community faced in the 20th century, but it is also a testament to the depth and resilience of Jewish tradition in the region.

A classic collection Likdosim Asher Baaretz by Rabbi David Laniado lists hundreds of notable Syrian scholars, each of whom contributed to the advancement of Torah learning.4 Here is a sampling of some of the best-known scholars, some of whom called Syria of home and some who just passed through there:

Rabbi Saadia Gaon (c. 882-942): Brilliant leader of the Babylonian Torah academy who transcribed the entire Torah into fluent Arabic and whose teachings and traditions remain central to Judaism today. While in Aleppo, he was instrumental in preventing the Jewish world from fragmenting into a situation that would involve different places using different calendars.

Rabbi Yosef Bar Yehuda (c. 1160–1226): A student of Maimonides, he was a noted scholar, physician, and philosopher in Aleppo, where he lived for many years. Maimonides wrote the Guide for the Perplexed to aid him in his efforts to reconcile his philosophical beliefs with faith in G-d. The Dayan Family: As their name implies (dayan in Hebrew is “judge”), successive members of the Dayan family, direct descendants of King David, served as rabbis in Aleppo for centuries.

Rabbi Shemuel Laniado (1605): Born in Aleppo to Sephardic parents, he studied under Rabbi Yosef Karo in Safed before returning to his hometown, where he served as chief rabbi for four decades. He was known as the Baal Hakelim because the titles of many of his published works began with the word keli.

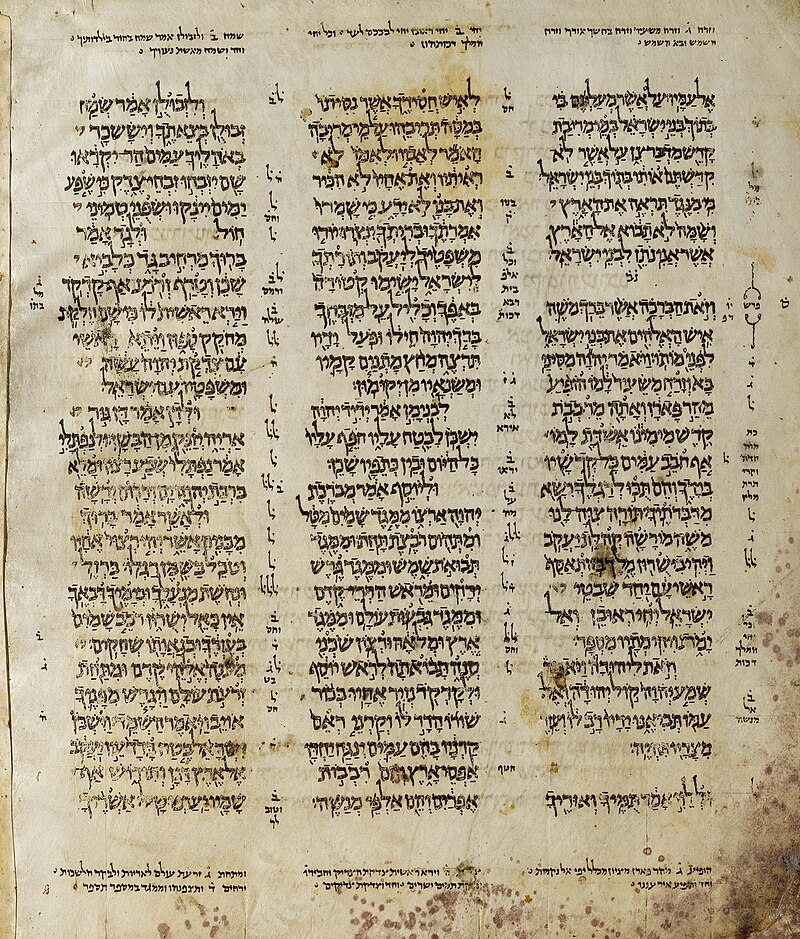

The Code of Aleppo. Credit: Shlomo ben Buya'a - Wikipedia

- For more than five centuries, the Jews of Aleppo were custodians of a priceless annotated text of the entire Tanach, known as Keter Aram Tzova (“The Crown of Aleppo”) or Code of Aleppo, so called because it was bound like a book (“codex”) as opposed to the traditional scrolling format.

The book – which was produced by the famous Ben Asher family of Tiberia – arrived in Damascus along with a descendant of Maimonides, who valued Keter and consulted it in his own quest to identify the most appropriate and accurate Torah text. Unfortunately, part of the Codex disappeared when the Great Synagogue of Aleppo was destroyed in 1947. The rest is now kept in the Sanctuary of the Book in Jerusalem.

- They were united (and dominated) by Sepharad

In the wake of the Catholic persecution of Jews in the Iberian Peninsula, which culminated in the expulsion from Spain in 1492 and the expulsion of the Portuguese in 1496, Spanish (Sephardic) Jews flocked to the relative tolerance of Muslim Arabia, including Syria. The Sephardim were originally separated from the native Jews (Musta'arabim), forming their own communal infrastructure and maintaining their own traditions. Over time, Sephardic customs and traditions dominated, and all Jews in Syria were identified as Sephardic.

- Their language was Arabic

Historically, Jews in Syria spoke Arabic, similar to their non-Jewish neighbors. When the Sephardim originally converged on Syria, they brought their language, Ladino, or Jewish-Spanish. However, after hundreds of years of becoming one with the Arabic-speaking locals, Ladino was largely forgotten among the descendants of the Spanish exiles.

- Some light an extra Chanukah candle

On Hanukkah, some Syrian descendants of Spanish exiles light a second shamash candle on Chanukiah, celebrating their ancestors' safe escape from Spanish expulsion.

Jews were persecuted until they disappeared in Syria

The 55,000 Jews in Syria after the establishment of Israel were severely restricted, and by 1964 only 5,000 remained. They were persecuted more severely and were not allowed to travel from town to town. Their every movement was watched by the Mukhabarat (secret police). The more they were tortured and confined, the more people were determined to leave Syria.

With information from Chabad