Over four million pages exist on the life of the Jews in Eastern Europe before the Second World War. These pages ran the serious risk of being burned by the Nazis and shredded by the Soviets. Miraculously, the biggest collection of documents in Yiddish survived.

This Jewish treasure is on display at the Center for Jewish History in New York, which also has an online version: https://museum.yivo.org/. It has become a reality thanks to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, which had the courage to digitise all the material.

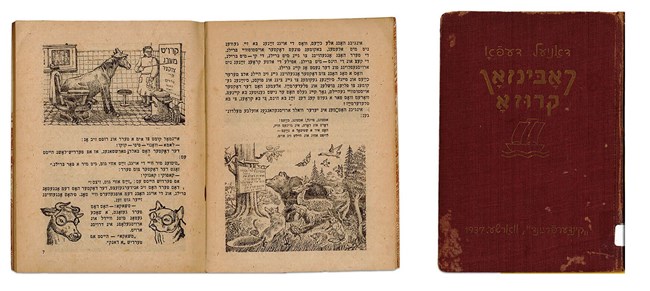

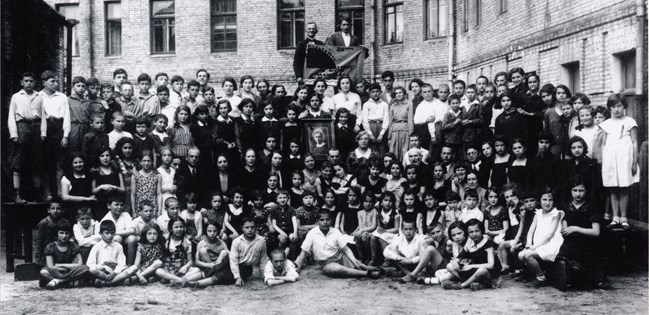

This task took seven years, cost the modest sum of seven million dollars (about six million euros), and was inaugurated last 27 January, the day marking the 77th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz extermination camp. This collection contains myriad artefacts and forms of expression, songs that were sung, movie posters from local cinemas, correspondence exchanged between family members, drawings by children who dreamed that they might, for instance, wish to study science, and other memorabilia.

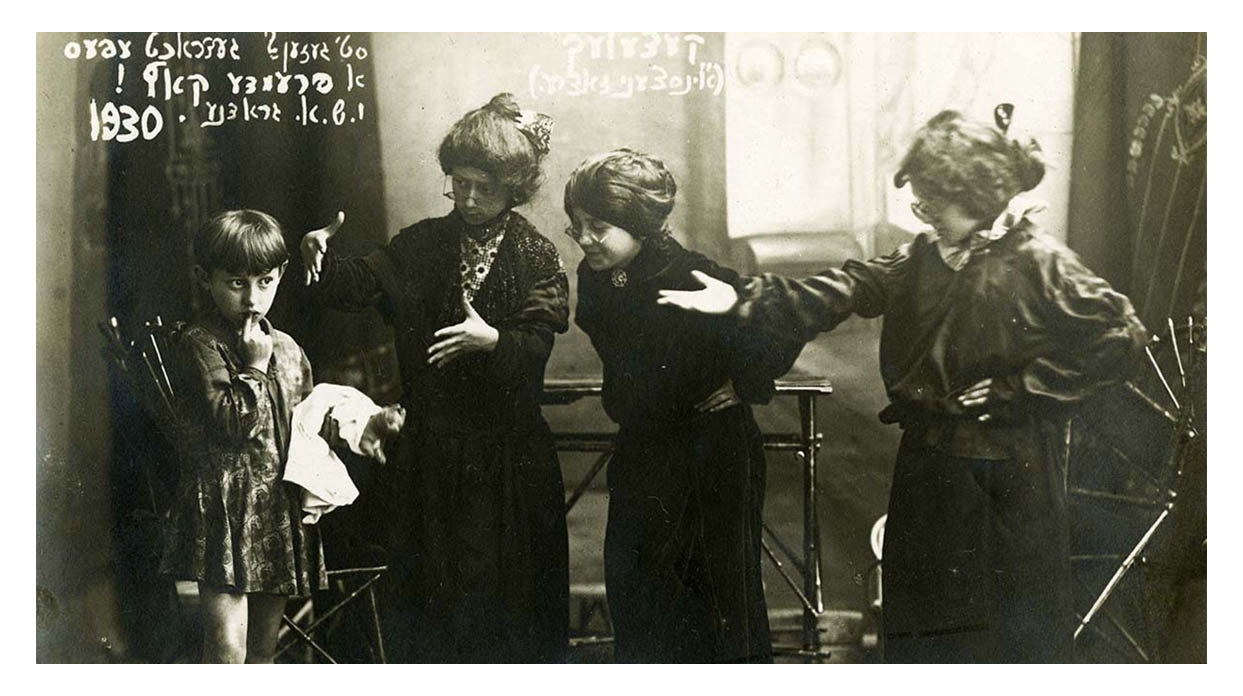

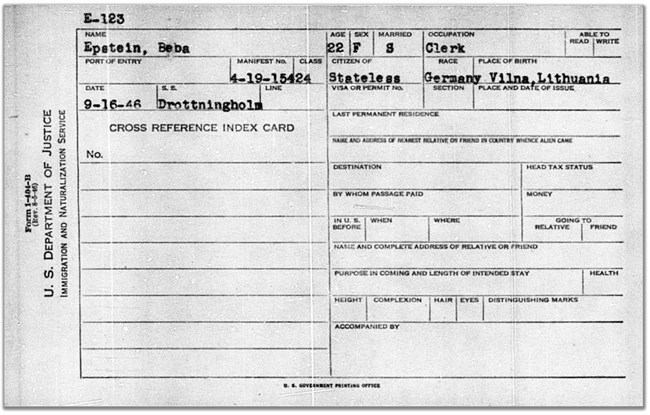

In the Diary of Beba Epstein, one of the documents that was digitised, this young girl mentions the first film she saw in Vilnius, Lithuania, in 1932. It was quite an unexpected story: a silent movie based on the novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, about race relations in the United States. In the opinion of Jonathan Nathan Brent, YIVO Executive Director, it shows the “ambition of the Jewish community and its interest in the outside world”, because these people “did not act as if they were so much water under the bridge”.

Founded in 1925 in Vilnius, Lithuania, YIVO (Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut, or Yiddish Scientific Institute) became the main teaching establishment of Yiddish studies, and of the history and culture of the Jews of Eastern Europe and of emigrant communities. Initially, the institute created the Zamler movement: notices were posted in all Jewish newspapers of the day to gather together everything that might be important in producing a reliable profile of Jewish life. The result exceeded all expectations. People from all parts of the world sent photographs of relatives, personal diaries, books, political pamphlets and so on. By 1941, it had been possible to amass the biggest collection of Jewish material. When the Nazis reached Vilnius they wanted to demolish and destroy the YIVO archives. Confrontations took place, but the assassins encountered a setback: they did not understand what was written on the documents and were forced to recruit learned Jews who could read and separate the wheat from the chaff. The poet, the great poet Avrom Sutzkever, was one of those recruited. These Jews decided that they would not give all the material to the Nazi executioners and hid papers in their clothes, even in their bodies.

The Nazis probably destroyed 30 to 40% of the archives. The rest was saved by miracle, heroically. The Jews who had been summoned to evaluate the documents took what they could from the YIVO building and buried it in the ghettos where they lived. If discovered they would have been shot. Other documents were passed on to non-Jewish friends, who swore that they would make them public as soon as the Second World War was over. When the war ended, the American army found them buried in tins in the ghettos. Soon they were on their way to YIVO in New York (European Jewish institutions had been annihilated) where they are to this day.

In 1948, the Soviets invaded Lithuania, when Stalin dictated to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, the Politburo, that Jewish identity should be destroyed. Another miracle occurred through a Lithuanian, António Opus, who secretly saved the documents: he hid them in St. George’s Church from 1948 to 1989.

The Government of Lithuania discovered them in 1991 and made a public announcement about this fact. There was a legal battle between New York who claimed them, and Lithuania, who refused to send them, until 2009 when Jonathan Brent travelled to Lithuania as part of the YIVO team and proposed that the preservation of the documents should be a joint project.

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research: https://www.yivo.org/