The history of the Jewish community of Oporto is much older than the official foundation of Portugal. It may even date back to the era of the Roman Empire, two millennia ago, after which the Jews coexisted with the Germanic tribes, the Muslims as well as the Christian Visigoths of the Reconquista.

The Jews of Oporto numbered a large quantity of doctors, as well as lawyers, goldsmiths, merchants, clothes peddlers, tailors, makers of passementerie, cobblers, market stall sellers and muleteers. The names include: Abeatar, Arieh, Azecri, Barchilan, Benatar, Ben Sasson, Davila, Elmaleh, Fadida, Gabay, Harari, Maimon, Nahmias and others.

In the 14th century, the mass killings of Jews in Toledo, Barcelona, Seville and other places gave rise to massive migration to Portugal, where the Jewish quarters were too small to accommodate so many people. Oporto was one of the cities that took in more refugees, having to face the ensuing problems, and the pattern continued of marriages between local Jews and Spanish Jews.

The situation was similar in 1492, at the time of the Jews’ expulsion from Spain. The first thirty Castilian families who reached Oporto, as well as others, all totalling some seven hundred souls, on the orders of King D. João II, were led by Rabbi Don Isaac Aboab, the greatest religious authority of the Jewish world at the time.

The garden of the Jewish Museum of Oporto has a stone epigraph in memory of the Chief Rabbi. We can only imagine the touching impact the arrival of this great Rabbi must have had on the city, where he lived in very favorable conditions until his death the following year. His funeral was conducted by his disciple, the famous rabbi, chronicler and mathematician, Abraham Zacuto, who made a huge contribution to the Portuguese Discoveries.

The Edict of Expulsion (1496) and the Inquisition (1536-1821) led to the death, emigration or forced conversion to Catholicism of the Jewish community. Synagogues, schools, monuments, epigraphs, documents and liturgical objects were destroyed. In Oporto, the Jewish quarter was designated, as it continues to this day, as “Vitória”, possibly alluding to the victory of Christianity over Judaism.

Officially, the Jewish community disappeared from Oporto, but many "New Christians" remained in the city at least until the beginning of the 17th century. In cooperation with the Catholic Diocese of Oporto, the current Jewish community dedicated the film 1618 to them. This film is based on a true story: the visitation of the Inquisition to the city of Porto in 1618. At the time the entire population was exhorted to denounce heresies under pain of excommunication. In a city where a large part of the population had Jewish ancestry, over one hundred New Christians, among others, were imprisoned, causing terror in the New Christian community, mass emigration and the near total destruction of the city’s economy. Friction between Porto’s judicial authorities, which had always been on good terms with the New Christians, and the inquisitorial visitation reached such a point that guards on horseback surrounded the ecclesiastical court, preventing the “heretics” in custody from being transported to Coimbra. The Visitor even traveled to Spain to give Philip II an account of the events transpired. The Jewish community disappeared from Oporto for centuries.

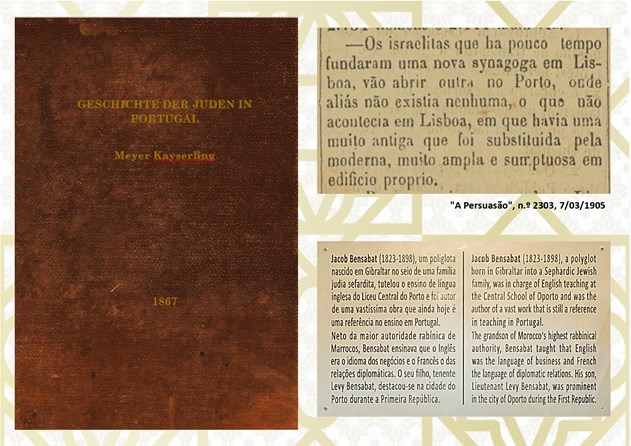

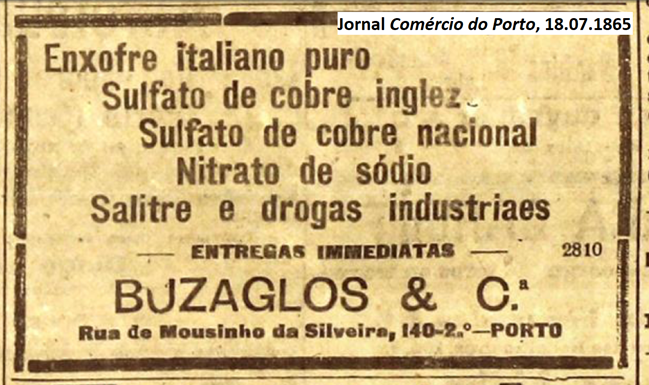

According to recent discoveries, which will soon be published in a book, the return of the Jews to this city occurred in the 19th century, a few years prior to the official abolition of the Inquisition in 1821. These were Sephardic Jews who came from Morocco, Gibraltar, Venice, London, Marseille, Lisbon, the islands of São Miguel and Terceira in the Azores, and elsewhere.

Their last names were, among others, Afflalo, Bensabat, Buzaglo, Abudarham, Abohbot, Ezaguy, Azavey, Bensabat, Benhanon, Benchimol, Serfaty, Ohayon and Azulay. As there was no Jewish cemetery in Oporto, these Jewish families were buried in the non-Catholic plots of Oporto’s municipal cemeteries, in the British cemeteries of Oporto, Lisbon and Figueira da Foz, and in the Jewish cemeteries of Lisbon, Faro and the Azores.

By the end of the 19th century, there were few Sephardic Jews living in Oporto. The Jewish community is mainly Ashkenazi now, particularly from Germany. It grew considerably during and immediately after the First World War, with the coming of Jews from Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, Poland and Lithuania. This new Ashkenazi community had last names such as Cohen, Reisman, Rosenthal, Hitzmann, Neumann, Friedman, Yanovsky, Sorin, Stern, Schuman, Bronstein, Levithin and others.

In 1923, the Ashkenazi families took in a Portuguese Jewish couple, both converted to Judaism, the husband a vigorous and intelligent army officer, who was a writer, publicist, researcher into Jewish and military history, member and speaker of the Commission of Military History, and specialized in national defense doctrines. Overcoming the introverted nature of seventeen of his brothers in faith of Central and Eastern Europe, Captain Barros Basto successfully convinced them to set up an association called “Comunidade Israelita do Porto” (CIP - Jewish Community of Oporto) similar to the “Comunidade Israelita de Lisboa” (CIL - Jewish Community of Lisbon).

The Jewish Community of Oporto (CIP) was created in the shadow of the foreign community of Jews in this city and it was headed by the only person who was really fit to do so: the Portuguese army officer. From 1926 onwards, Basto headed a personal project, with the aid of the London Sephardic community, to try and convert Marranos as a whole to Judaism, for there were thousands around the country at the time. This attempt resulted in the construction of the large Kadoorie Mekor Haim synagogue paid for by the Sephardic diaspora, but unfortunately not a single official Jew in the light of Jewish law. In cooperation with the Catholic Diocese of Oporto, the current Jewish community dedicated the film Sefarad to Captain Basto and Marranism, a religion of its own that involved elements of Christianity and Judaism.

During and after its construction, the synagogue building was placed in the hands of the city’s few Ashkenazi families and it played a key role in sheltering refugees during the Second World War, which was followed by decades of depletion and desolation.

Although throughout its century-long history the modern Jewish community of Oporto has always had Jews in sufficient numbers in the light of Halacha to constitute minyan, the fact is that for decades on end, it never fulfilled any of the functions that might be expected from a Jewish organization legally recognised by a State. Similarly, the synagogue failed to perform the mission that might be expected from an enormous building possessing all the conditions to be a regional Jewish center.

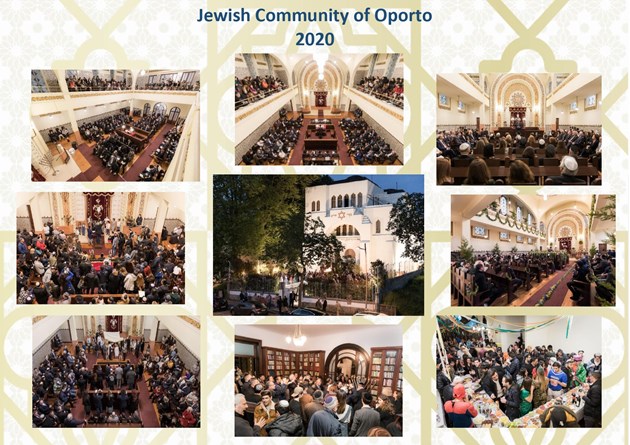

Only in the 21st century, largely as a result of the 2013/2015 legislation that gave Portuguese nationality to Sephardic Jews, the reality changed: the community rapidly grew to comprise hundreds of Jews from thirty countries. Some were Sephardic, with last names such as Cohen, Levi, Zekri, Mizrahi, Sheni, Dror, Mocatta, Attias, Bitton, Dias and Amar; others were Ashkenazi, and they achieved full Jewish life, including a rabbinical court, kosher restaurants, museums, films about its millenary history, and departments to ensure the smooth running of the organization.

Anyway, as the history of the Jews in Europe has taught us that where there are many Jews today, there may be none tomorrow, now the laws of the Jewish community of Oporto establish that should it end one day, its properties and assets shall revert to the Jewish Agency.