In 1143, when King D. Afonso Henriques received recognition of Portugal as an independent kingdom, the Jews had been present on the Iberian Peninsula for over a millennium. Consequently, it is hardly news that Jewish quarters existed in Lisbon.

In addition to the first Jewish quarter, in Pedreira neighbourhood, which by 1260 had a synagogue, we know of at least three Jewish quarters; Judiaria Velha or Judiaria Grande (Old or Large Jewish quarter), which occupied Santa Madalena neighbourhood, and had a synagogue, Sinagoga Grande, built in 1307, in Rua da Princesa, on the corner with Rua dos Mercadores; Judiaria Nova or Judiaria Pequena (New or Small Jewish quarter), restricted to one single street, then called Rua da Judiaria or Rua das Taracenas or Tercenas; and Judiaria da Alfama, also known as Judiaria Pequena da Torre de S. Pedro (Alfama or Small Jewish quarter of St. Peter’s Tower) which had a synagogue built in 1373/74, following the tragic invasion of the Jewish quarters by the armies of King Henrique II of Castile when he attacked Lisbon in 1373.

Until the 1496 Edict of Expulsion, the Jews were relatively tolerated. The following year, the “General Conversion” abolished and proscribed Judaism in Portugal. With the exception of those who fled if they could, the former Jews and their descendants were now considered nominally Catholic, that is, New Christians, legally obligated to practice Catholicism exclusively. After 1536, they were subjected to trial by the Inquisition, should they continue to observe the Law of Moses in secret. The return of the Jews to Portugal, in the late 18th and 19th centuries was undoubtedly a prosperous consequence of the measures taken by the Marquis de Pombal. In 1772, his decision to do away with the discrepancies between New and

In addition to the first Jewish quarter, in Pedreira neighbourhood, which by 1260 had a synagogue, we know of at least three Jewish quarters; Judiaria Velha or Judiaria Grande (Old or Large Jewish quarter), which occupied Santa Madalena neighbourhood, and had a synagogue, Sinagoga Grande, built in 1307, in Rua da Princesa, on the corner with Rua dos Mercadores; Judiaria Nova or Judiaria Pequena (New or Small Jewish quarter), restricted to one single street, then called Rua da Judiaria or Rua das Taracenas or Tercenas; and Judiaria da Alfama, also known as Judiaria Pequena da Torre de S. Pedro (Alfama or Small Jewish quarter of St. Peter’s Tower) which had a synagogue built in 1373/74, following the tragic invasion of the Jewish quarters by the armies of King Henrique II of Castile when he attacked Lisbon in 1373.

Until the 1496 Edict of Expulsion, the Jews were relatively tolerated. The following year, the “General Conversion” abolished and proscribed Judaism in Portugal. With the exception of those who fled if they could, the former Jews and their descendants were now considered nominally Catholic, that is, New Christians, legally obligated to practice Catholicism exclusively. After 1536, they were subjected to trial by the Inquisition, should they continue to observe the Law of Moses in secret. The return of the Jews to Portugal, in the late 18th and 19th centuries was undoubtedly a prosperous consequence of the measures taken by the Marquis de Pombal. In 1772, his decision to do away with the discrepancies between New and

Old Christians, extinguish the privileges of the tribunals of the Holy Inquisition and convert them into State courts, played a key role to ensure that the descendants of the Jews forced into exile were able to return to their emotional homeland.

Although religious freedom was gaining ground, the Inquisition would only be derogated on 18 December 1821. It was only five years later, in the reign of King D. Pedro IV and at the time of the Constitutional Charter, that freedom of worship was finally acclaimed, a freedom applicable only to foreign citizens. This fact meant the following: the Catholic religion was the only religion authorised, meaning that all Portuguese nationals had to be Catholic. However, an exception was devised which was suited to attracting Jews: said foreign citizens could belong to and practice a religion other than Catholicism.

There were constant appeals to encourage the immigration of Jews who had once been forced to leave Portugal. Many requests were made in this regard, by the State itself and by private individuals. The first and inaugural wave brought Jews from Morocco, London and Gibraltar. They settled in Faro and Lisbon, in the Azores and Madeira and, as recently discovered, also in Oporto.

Having created stable conditions these Jews, overwhelmingly dedicated to trade, wished to organise their Jewish life. The first concern was to find land where they could bury their dead. This priority was achieved by the group of Jews from Gibraltar: immediately following their arrival in Portugal in 1801, they bought a small plot in the British Cemetery in the Estrela neighbourhood in Lisbon. The first grave was that of José Amzalaga who died on 26 February 1804. The Jews of Lisbon were buried in this holy ground until 1865.

The second priority was to discover places where they might worship. Initially, private houses were used for this purpose, but as soon as conditions allowed, dedicated spaces were found for this objective: synagogues.

From one house to another. It is hardly exaggerated to say, “Where you have two Jews, there are always three opinions”. This saying is quite fitting when one considers how many synagogues there were in Lisbon throughout the century. Some were even open at the same time.

In 1810, we know of three separate houses: one in Largo do Campo Santo, in the home of Simão Cohen. In 1813, we see the emergence of the very first public synagogue, that is, a place totally given over to prayer. Located in Beco das Linheiras, its name initially was Shaar Hashamaim (Gate of Heaven) until it was changed to Etz Haim (Tree of Life).

Although the fires of the Inquisition no longer existed, the founder of this synagogue, Rabbi Abraham Dabella, was denounced by a neighbour. The Inquisitor complied with the laws of the time and paid no heed to this occurrence. This was discovered by Herman Prinst Salomon (1931- 2021), a Dutch-American linguist and historian who specialised in the history of the Portuguese Jews, the New Christians and the Inquisition. While this synagogue was still active, another one opened in Travessa da Palha, founded by Salomão Mor José. After his death, the regulars moved to a house in Travessa do Ferragial de Baixo.

1860 saw the establishment of Etz Haim II synagogue in Beco dos Apóstolos. It belonged to seventeen families who held right of admission and even of expulsion of the traditional rowdy elements. The fact that the space was much larger than any other synagogue led to it being known by the name of the “Large Synagogue”. It differed from the others because its attendants nourished a feeling of community that was not restricted merely to worship. It included departments in addition to places of prayer, such as the Shechita section (animal slaughter) and Somej Nophlim (Help for the Needy).

These families (Amzalak, Anahory, Abecassis, Seruya, and others) wanted to buy land on Rua da Palma on which to build a synagogue. Funds were raised but were not used for that purpose. Even so, they were able to buy land on Calçada das Lajes, which today houses the Jewish Cemetery of Lisbon. We could say that the Jewish Community of Lisbon was born at that time.

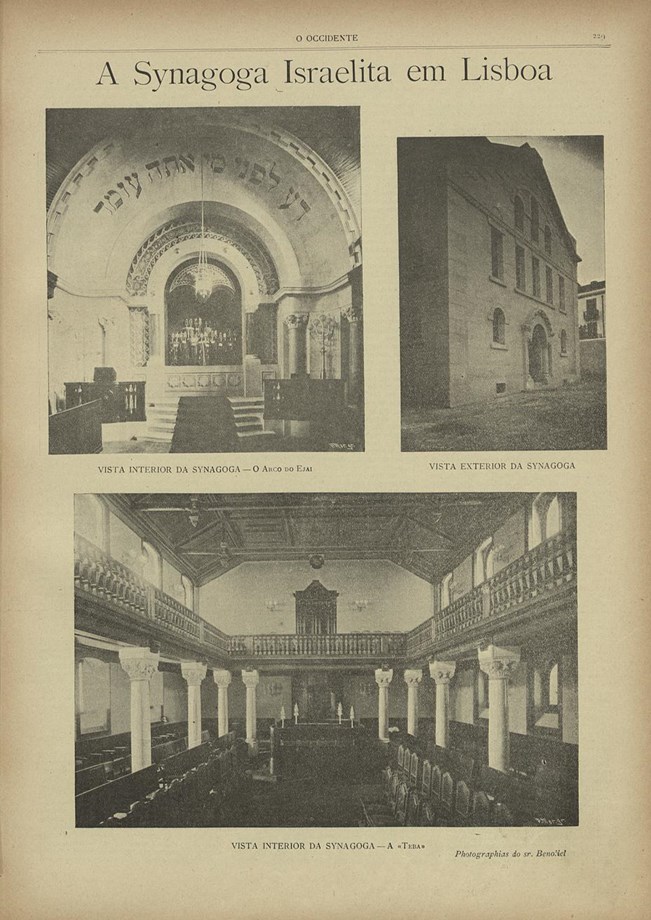

The dream of building the synagogue was postponed but not for long. On 23 August 1901, a deed of purchase was signed for a plot of land along the extension of Rua Alexandre Herculano, by several members of the Jewish Community of Lisbon. One year later, these men signed another deed gifting the land to the community headed by Leão Amzalak. In a mere twelve months the ceremonial laying of the keystone of the synagogue took place. Its name was a unanimous choice: Shaare Tikvah (Gates of Hope). Joaquim Bensaúde – Leão Amzalak’s technical adviser and later honorary president – chose Miguel Ventura Terra, an architect who was famous at the time, to draw up the plans, which by State decree had one insolent condition: the synagogue could not have a door giving onto the street.

Unable to fight this unusual demand, which matched the reference to Portuguese citizens being forbidden to adopt any faith other than the Catholic religion, the innovative Jews acquiesced and commissioned the building of their temple.

On Wednesday 18 May 1904, the Jewish Community of Lisbon met at the old synagogue on Beco dos Apóstolos nº 6, second floor. Here, Rabbi Levi Bensimon conducted the religious service, a prayer of farewell was said and then each person carried a Sefer in a carriage to the new synagogue. The date heralded a new era: a new building was raised, the dark pages of history were increasingly in the past, the first synagogue to be built from scratch in Portugal, three hundred years after the Inquisition was set up, became reality.

After 1940, Shaare Tikvah was physically deteriorating. However, times were not right for a remodelling. The community had its hands full with innumerable refugees fleeing the countries where Nazism prevailed and engaged in killing. Two years after the end of Shoah, the synagogue closed for structural works and opened the following year.

A new face. 100 years after its inauguration, 45 years after the first refurbishment, and having again been closed for one year, Shaare Tikvah Synagogue reopened with a new look, adapted to modern times, although care was taken not to damage or conceal the original architecture. Some of the previous restoration work was enhanced: the renowned architect Ricardo Bak Gordon, responsible for the project,

was able, among other significant alterations, to virtually overthrow the imposition made in the early 20 th century, although the synagogue still does not have a door onto the street: that would have meant building a new synagogue. But now, anyone walking past Rua Alexandre Herculano nº 59 can relate the Stars of David to Judaism and see the name Shaare Tikvah stamped in Hebrew characters.