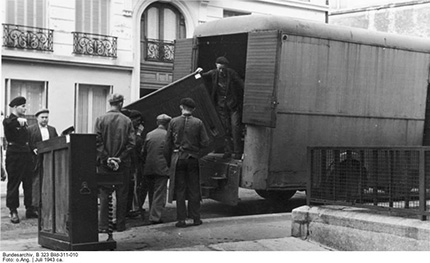

Prisoners from the Drancy camp loading stolen pianos from families of deportees. Credit: Bundesarchiv

The French association Music and Spoliations, founded by historian Pascale Bernheim and lawyer Corinne Hershkovitch, does important work for the reconstruction of history and preservation of memory regarding the Jews and the Second World War. Since 2017, the association has been researching the provenance of musical instruments and documents, identifying objects that disappeared during the Nazi occupation and leading them to their true owners.

The theft of musical instruments and handwritten scores was common practice during the German occupation. The Nazi regime had a team called Sonderstab Musik (Music Commando), which was sent to France in August 1940 to collect these objects. However, not all missing musical instruments were stolen. Some of them were lent or sold for symbolic prices by desperate Jews, who handed them over to “trusted guardians” – usually neighbors or acquaintances.

As stated by Pascale Bernheim for Radio France, "the work of memory is really what drives us at the Association Musique et spoliations. Paying homage to the man, the artist, the musician, the amateur who was able to play the instrument is important for us, just like tracing, finding the pedigree of musical instruments".

Beethoven's handwritten score was returned to the descendants of the Petschek family. Credit: AP

The search for the true owners is running out of time, as there are fewer and fewer living witnesses – who are not restricted to Holocaust survivors, but also to museum employees, musicians, businessmen, etc. According to Karel Janicek, Associated Press correspondent, an example of successful action by Music and Spoliations was the recovery of a handwritten score by Beethoven, which was returned to descendants of the Petschek family – the richest family in Czechoslovakia before World War II.

In 1939, the Petscheks tried to send the score abroad, but the move caught the attention of the Gestapo, who took the work and asked an expert from the Moravian Museum in Brno, Czech Republic, to verify the authenticity of the document. The specialist denied authorship, to prevent the score from being in the possession of the Nazis and, since then, the document has remained in the Museum.

“We’re sorry about losing it, but it rightly belongs to the Petschek family”, museum curator Simona Sindelarova said.

The association is in talks to returned the violin to the National Museum in Warsaw. Credit: Pascale Bernheim

Not all cases, however, are simple to resolve. A violin made by the luthier Giuseppe Guarneri in 1706 and which in 1939 belonged to the Jewish merchant Felix Hildesheimer has been the subject of debate between his descendants and the Hagemann Foundation. Another example is a Stradivarius violin made by Antonio Stradivari in 1719 and owned by Henryk Grohman, a Jewish merchant from Lodz. The violin was in the possession of the National Museum in Warsaw when it disappeared. Recently, the musical instrument has resurfaced, after its current owner reached out to Music and Spoliations to verify that the object is the instrument sought. The association confirmed and is now in negotiations to bring the object back to the National Museum in Warsaw.