The weakness of the Inquisition and its formal end, announced at a session of the General Cortes on 31 March 1821, revived the presence of the Jews who, for two hundred and eighty five years had been silenced and threatened by fire. For reasons linked to the Covid 19 pandemic it was impossible to celebrate the bicentenary of the End of the Inquisition in Portugal. This next 31 March, therefore, the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Inquisition will be marked by a number of initiatives to commemorate this historic date.

- Academia Montsefarad, Academia para o Estudo da História e Património sefarditas de Trás-os-Montes, on 31 March will mark the 201 years of the extinction of the Inquisition in Portugal at a conference open to the public. The Bicentenary of the End of the Inquisition in Portugal will recall the 200th anniversary of the extinction of the Court of the Holy Inquisition.

Chaves City Library

Address: Largo General Silveira - 5400-516 Chaves

31 March, 4 pm

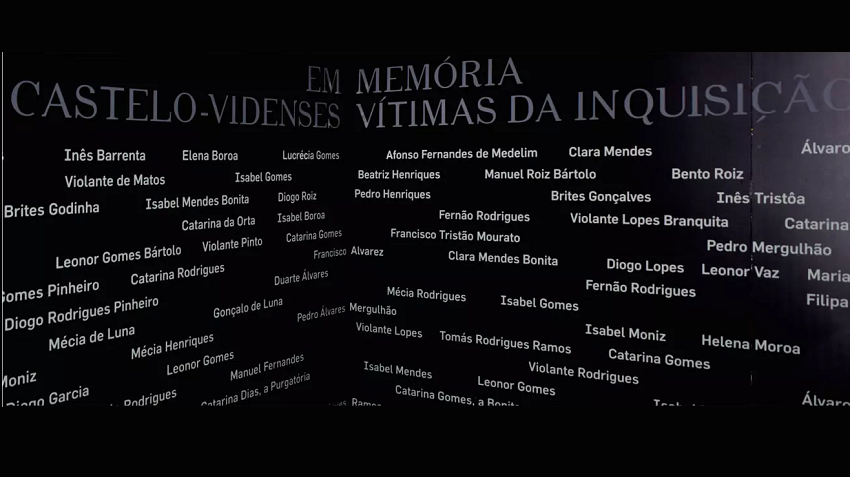

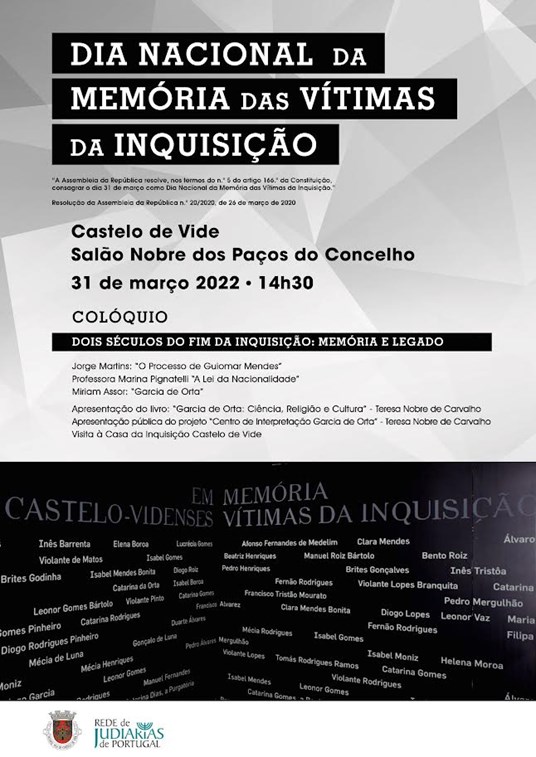

- Castelo de Vide Municipality has organised a seminar on “Two Centuries of the End of the Inquisition: Memory and Legacy (Dois Séculos do Fim da Inquisição: Memória e Legado). One of the speakers is Jorge Martins, Doctor of Contemporary History and the author of many works on Jewish studies and the Inquisition, responsible for setting up the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Inquisition. There will also be the presentation of a book and of the Garcia de Orta Interpretation Centre.

Salão Nobre do Paços do Concelho / Town Hall

R. de Bartolomeu Álvares da Santa

31 March, 2.30 pm

Inquisition, Intolerance

The Portuguese Inquisition, as explained by renowned expert Professor Herman Prins Salomon (1930-2020) , began its activity in 1536. It encompassed new Christians, sodomites, Moors, Lutherans, Erasmians, non-believers, elches (Spanish and Portuguese who converted to Islam while in captivity), priests who used the confessional for seduction purposes, bigamists, blasphemers, witches, and corrupt people in the institution. Of the 40 thousand Inquisition processes in Portugal, about 38 thousand involved new Christians.

The “General Conversion” of 1497 had abolished and proscribed Judaism in Portugal. All former Jews and their descendants were now deemed to be nominally Catholic, that is, new Christians, legally compelled to practice only the Catholic religion. After 1536, they could be tried by the court of the Inquisition, should they continue to observe the “Law of Moses” in secret. The expression “Law of Moses” included precepts and customs of non-biblical origin, deemed to be “Jewish” by the Inquisitors.

The flames of the Inquisition, the scourge first lit by the Catholic Kings with the publication of the 1st Inquisition Law in Spain in 1484, soon arrived and spread in Portugal. After Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon had expelled the Jews from Spain in 1492, about 60 thousand Jews who refused to convert to Christianity emigrated to Portugal. Influenced by important Jews at court, King D. João II welcomed them with semi-open but pitiless arms, for he forced them to pay eight gold ducats – a very large sum at the time – to remain on Portuguese soil (those who could not pay that amount had their assets confiscated by the Crown), while underage children of the Jews were vilely exiled to the Island of São Tomé. On the death of King D. João II, he was succeeded by his first cousin, King D. Manuel I, who, on 1 March 1497, decreed the expulsion of the Jewish Community in Portugal through a law that came into force almost immediately: “so that all should be considered, favoured and treated as the old Christians, with no distinction or separation of any sort”. To prevent the exodus of so many people from the kingdom, King D. Manuel I decreed the forced conversion of Moors and Jews to Christianity in the time limit of ten months, while those under 14 years of age had to be handed over to the Christians for compulsory baptism.

This evil carried within it vestiges of the plague: the king, erroneously described as the “Fortunate”, was in Muge on 5 December 1496 when he signed the Letter Patent, in which he ordered all “heretics” (Jews and Moors) to leave Portugal. This repulsive measure, set out in the marriage agreement of D. Manuel I and Princess Isabel of Aragon, then heiress to the Catholic Kings, was an attempt to homogenise Catholicism in the Iberian Peninsula. Fulfilment of these wretched matrimonial injunctions meant the end of those times, the golden era of a once multicultural nation where Christians, Muslims and Jews lived peacefully together, a nation of Portuguese, Latin, Arab and Hebrew speakers. On 21 April 1499, a charter forbade the new Christians to leave the kingdom, particularly when they left with their families, under penalty of their assets being seized. Men were only allowed to leave the country on business, provided their children and wives stayed at home. On Sunday, 19 April 1506, during Easter, a popular uprising led by Dominican friars against the new Christians lasted for three blood-filled days. Moved by religious fanaticism, the mob persecuted, raped, tortured and killed hundreds of people accused of being Jewish. Men, women and children were tortured, massacred, raped and burned at improvised stakes in Rossio. Among other “evils” the Jews were accused of deicide and of being the cause of the terrible drought and plague sweeping the country. This episode, known as the Lisbon Massacre, highlighted the growing antisemitism and led many families to abandon Portugal. Some new Christians, however, remained faithful to their original religion (and became known as Marranos or crypto-Jews) and invented ways to hide their religious conviction. The failure of the seriousness of many conversions led King D. João III to set up the Inquisition in Portugal in 1536, and the establishment of a policy marking the difference to new Christians. Faced with the spectre of the court of the Inquisition designed to defend the Catholic faith, keeping watch over, persecuting and condemning all others suspected of practising other religions, the new Christians, who were mainly Jews – about 1500 mortal victims of the Portuguese Inquisition were new Christians, while of the 40 thousand processes of the Portuguese Inquisition about 38 thousand involved new Christians – never again found peace in Portugal. Some continued to practice Judaism secretly, others fled to the Netherlands, Constantinople, North Africa, Salonika, Italy and Brazil, maintained secret ties and supported the Portuguese new Christians. In addition to having their assets seized, they were also affected by having to present certificates of blood purity to have access to public, military or church positions, when kept them away, as they had inquisitorial confirmation.

Although officially extinguished in March 1821, the Portuguese Inquisition had lost force during the second half of the 18th century under the influence of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Mello, the Marquis of Pombal (1699-1782), who was against these inquisitorial methods. Added to Pombal’s actio,n the Age of Enlightenment was crucial in making inquisitorial practices disappear in Portugal. The only trace of the two hundred and thirty eight years of darkness are the archives, more than thirty-five thousand processes, lodged at the Torre do Tombo.