Exactly 90 years ago, on September 15, 1935, Nazi Germany enacted the Nuremberg Laws, decrees that institutionalized discrimination against Jews and marked one of the darkest moments in modern history.

The laws were formalized during the Nazi Party Congress in the city of Nuremberg and established racial criteria to determine who could be considered a German citizen. Among other restrictions, they prohibited marriages and sexual relations between Jews and “pure-blooded Germans.”

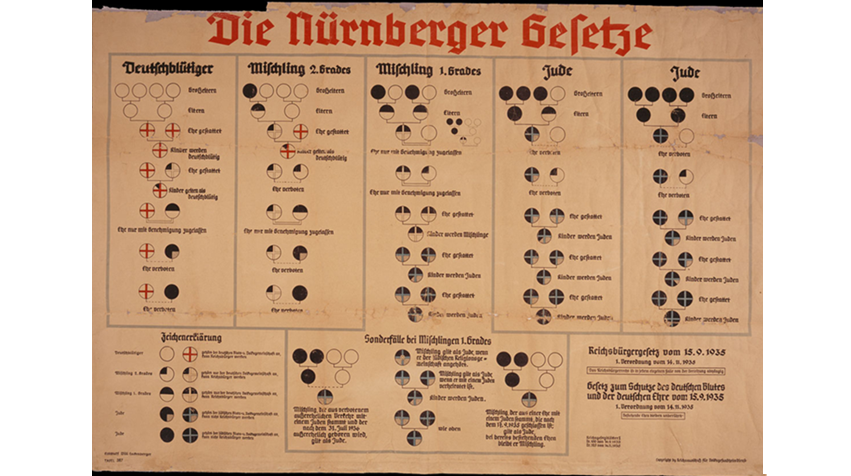

People were classified according to the number of Jewish grandparents: those with three or four Jewish grandparents were considered full Jews (“Volljuden”), those with two were “Mischlinge of the first degree,” and those with only one Jewish grandparent were “Mischlinge of the second degree.”

The Nuremberg Laws represented a crucial stage in the escalation of persecution against Jews, serving as a transition from social prejudice to institutionalized oppression. By turning discrimination into law, the Nazi regime created a legal foundation that justified increasingly violent actions, laying the groundwork for the Holocaust. This progression shows how legal oppression can evolve into crimes against humanity when the state uses the law to legitimize the exclusion and persecution of entire groups.

The Law of Return: The Right to Live in the Jewish State

The State of Israel, through the Law of Return, applies a similar criterion of descent: it grants citizenship to Jews and their descendants with up to one Jewish grandparent. The historical parallel is clear: while the Nuremberg Laws were designed to exclude and persecute, the Law of Return seeks to include and protect, offering a national homeland to people who have been historically persecuted—even if, according to religious law (Halacha), some of these individuals are not considered Jewish.

Credit: The Librarians

Other significant moments triggered by the Nuremberg Laws

According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia

August 17, 1938: Law on the Alteration of Family and Personal Names

On August 17, 1938, the Law on the Alteration of Family and Personal Names established new naming requirements for Jews in Germany. This law mandated that Jews could only be given certain approved first names. New Jewish parents had to choose a name from a government-approved list. Additionally, any Jew who did not already have a name from this list had to add an additional first name: “Israel” for men and “Sara” for women. Individuals had to register their new names with government offices and use both their given and added names in official and business transactions.

October 5, 1938: Decree on Jewish Passports

The Nazi regime invalidated the German passports of all German Jews. To regain validity, German Jews had to submit their passports to the authorities to be stamped with the letter “J.” The decree specified that this applied to the passports of German Jews as defined by the Nuremberg Laws.

September 1, 1941: Police Regulation on the Identification of Jews

Starting in September 1941, all Jews in Nazi Germany were required to wear a special yellow badge in public. The badge was a palm-sized, yellow six-pointed star outlined in black, representing the Star of David.

The star had to have the word “Jude” (Jew in German) written in the center and be visible whenever a Jew appeared in public. Specifically, Jews were required to sew this yellow star onto the left side of their chest. This regulation applied to all German Jews, as defined by the Nuremberg Laws, aged six and older. Germans classified as Mischlinge, whether of the first or second degree, were not required to wear the star.